-

-

-

Loading

Loading

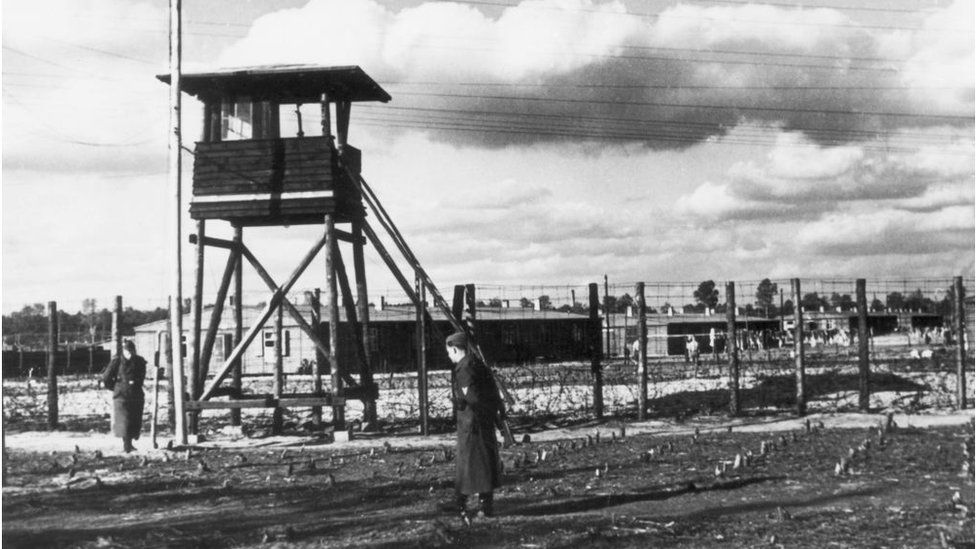

During World War Two, many individuals were forcibly held captive. Service members who were captured in battle were deemed prisoners of war, while civilians who were seen as a threat to the state were placed in internment camps. While stories of physical escapes during this time are well-known and often depicted in film and literature, there is another type of escape that is not as widely recognized – the escape within one's own mind. The National Archives in Kew is currently hosting an exhibition that showcases the extraordinary stories of these mental escapes. The exhibition includes various forms of artistic expression, such as patchwork quilts, an orchestra of humming women, a dedicated dog, and drawings of imaginative aircraft. One notable individual featured in the exhibition is Ronald Searle, the creator of St Trinian's. During the war, Searle was held as a prisoner by the Japanese, first in Changi Prison and then in the Kwai jungle where he worked on the Siam-Burma Death Railway. Despite suffering from various ailments, including dysentery and malaria, Searle had an unwavering desire to document his experiences through drawing. He considered this creative outlet as a "mental lifebelt" that helped him cope with the harsh realities of his captivity, even though it was a dangerous activity that could have cost him his life if discovered by the Japanese soldiers. The exhibition also includes the story of nine-year-old Olga Morris and her family, who were living in Malaya before being captured by the Japanese in Singapore and interned in Changi camp. Despite the difficult conditions within the camp, the internees came together and formed a secret Girl Guide group. As a surprise for their guide leader, the girls created a patchwork quilt using scraps of fabric, including pieces of rice bags. Another incredible story featured in the exhibition is that of Guy "Griff" Griffiths, a Royal Marine pilot who was captured by the Germans and held at Stalag Luft III, the setting for the famous movie The Great Escape. Griffiths used his artistic skills to create false paperwork for other prisoners of war and even drew counterfeit Allied aircraft, leaving the drawings for the guards to find. Also showcased is the bond formed between Leading Aircraftman Frank Williams and an English Pointer named Judy. While held captive in an Indonesian camp, Frank managed to hide Judy from the guards, and the two became inseparable. They even assisted in cutting through the Sumatran jungle, creating a route for a new railway. After the war, they were reunited and Judy accompanied Frank on his new Royal Air Force duties. Margaret Dryburgh, a missionary and teacher, attempted to escape the advancing Japanese forces but was captured and taken to an internment camp in Sumatra. There, she founded a vocal orchestra with another internee, Norah Chambers. Instead of using traditional instruments, the women relied on humming and consonants to create music. Dryburgh also composed The Captives Hymn, which was sung every Sunday at the camp and is still performed worldwide. The exhibition at the National Archives in Kew will be open to the public until July 21 and offers a glimpse into the remarkable stories of these individuals who found solace and escape within their own minds during a time of confinement and hardship.